From 1774 to 1789, the American colonies were controlled by the First Continental Congress, which convened in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was the de facto national government at the time and represented the original 13 colonies. However, following the Continental Congress came the Confederation Congress, which served from 1781 to 1789. It was in charge of running the first federal government in the United States each had a President.

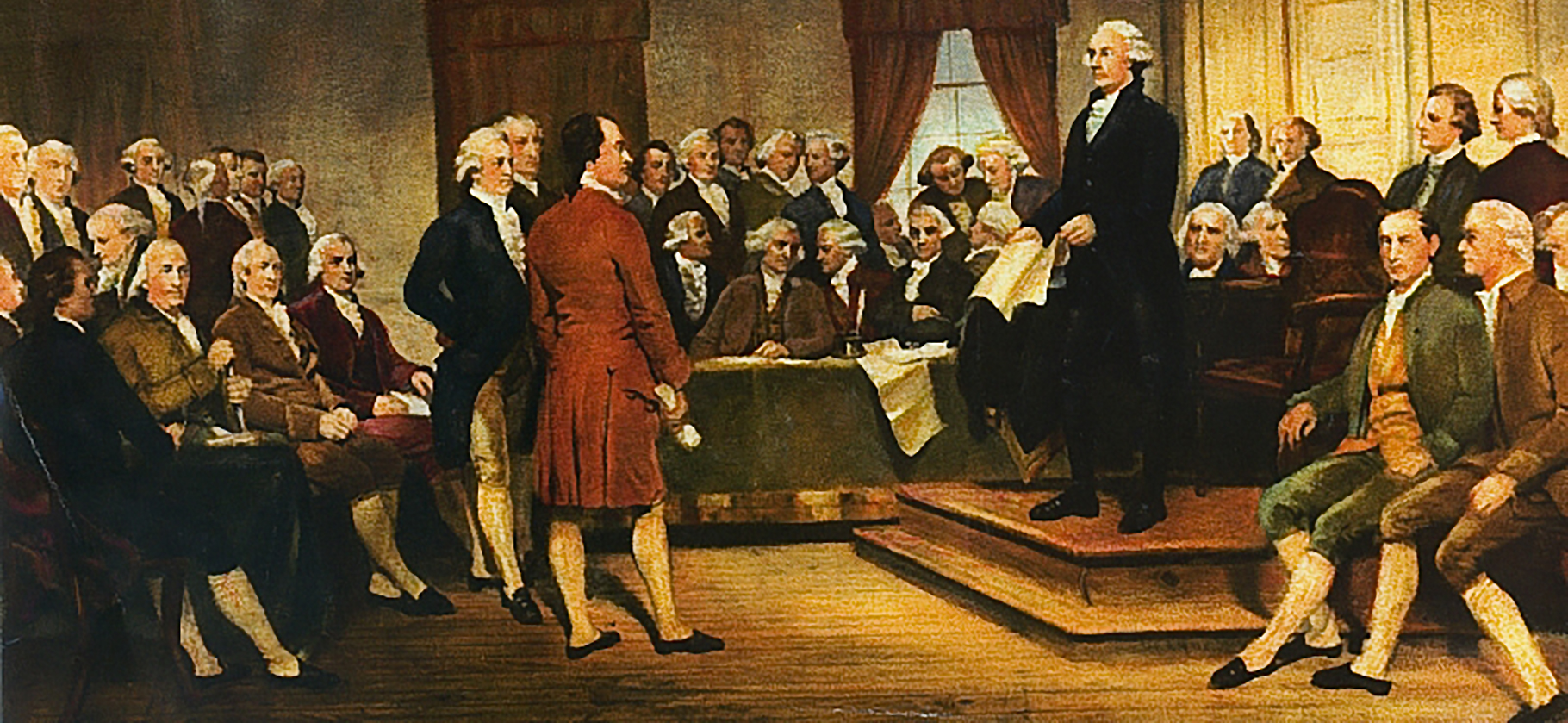

The relationship between the American colonies and Great Britain changed dramatically once the Continental Congress was formed. The growing frustration of the colonists with British policies and tyranny gave rise to this movement. Colony delegates met to air their issues and formulate a coordinated reaction. Although the First Continental Congress was crucial in setting the stage for subsequent events, it was the Second Continental Congress, which met in 1775, that took the initiative in bringing the colonies to independence. On July 4, 1776, it produced the Declaration of Independence and created the Continental Army, with George Washington as its first commander.

The Articles of Confederation, the original constitution of the United States, were drafted by the Confederation Congress, which included representatives from all thirteen states. In 1777, the Articles of Confederation were finalized, and by 1781, all 13 states had accepted them. However, the federal government was weak in comparison to the states; it had little taxing authority and was unable to properly regulate commerce, both of which contributed to a number of economic difficulties.

The Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress were not perfect, but they did accomplish several important things that changed the path of American history. On July 4, 1776, the thirteen colonies officially declared their independence from Great Britain by adopting the Declaration of Independence. The Confederation Congress established the Continental Army, appointed George Washington as its commander-in-chief, and managed the war effort in coordination with the numerous state militias, all of which were crucial to the success of the American Revolution.

Before George Washington, there were eight other presidents who presided over the Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress.

Randolph, Peyton, in 1774: As president of the Continental Congress. He presided over the meeting and assisted in drafting petitions to King George III detailing displeasure with British policy.

President of the Second Continental Congress in 1774 was Henry Middleton. During the early phases of the Revolutionary War, he was instrumental in handling the operations of Congress.

John Hancock: From 1775 to 1777, Hancock presided over the Second Continental Congress. He was instrumental in rallying support for the Revolutionary cause and was the first to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Henry Laurens: In 1777, Laurens led the Continental Congress as its president. He was instrumental in obtaining foreign support for the American Revolution, especially from France.

John Jay: presided over the Continental Congress as president in 1778. He was instrumental in the finalization of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which acknowledged American independence and marked the end of the Revolutionary War.

From 1779 to 1781, Samuel Huntington presided over the Continental Congress as its president. During a vital phase of the conflict, he was instrumental in directing Congress’s operations.

The Continental Congress was led by Thomas McKean, who was president from 1781 to 1782. He was crucial in directing the American Revolution’s military and financial activities.

The Confederation Congress was led by John Hanson, who served as president from 1781 to 1782. He was the first person to be officially known as “President of the United States in Congress Assembled” under the Articles of Confederation.

Eight presidents of the Continental and Confederation Congresses guided the young nation through its formative years, paving the way for George Washington’s presidency and the establishment of a more robust federal government.

George Washington was unanimously elected president of the United States in the 1788-1789 election. The electors from 10 of the 13 states cast their votes for him, making him the only president in American history to be elected without opposition. The electors from North Carolina and Rhode Island did not participate in the election, as they had not yet ratified the Constitution.

The electors who voted for Washington were:

Connecticut: Oliver Wolcott, Roger Sherman, and William Samuel Johnson

Delaware: John Dickinson and Richard Bassett

Georgia: William Few and Abraham Baldwin

Maryland: Daniel of St. Thomas Jenifer, John Henry, and Daniel Carroll

Massachusetts: John Hancock, Samuel Adams, and Elbridge Gerry

New Hampshire: John Langdon and Nicholas Gilman

New Jersey: William Paterson, Jonathan Dayton, and Richard Stockton

Pennsylvania: Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Mifflin, and Robert Morris

South Carolina: Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, John Rutledge, and Charles Pinckney

Virginia: Edmund Randolph, George Wythe, and James Madison

Washington’s unanimous election was a testament to his popularity and the respect he commanded among his fellow citizens. He was seen as a brilliant military strategist and a wise leader, and he was widely believed to be the best man to lead the new nation.

Among the Articles of Confederation’s many flaws were a lack of a powerful executive branch, ineffective taxation, and inadequate regulation of commerce. The Articles were abandoned because they were inadequate for establishing a strong national government, which in turn caused monetary difficulties, difficulties in generating finances, and difficulties in maintaining law and order.

The Continental Congress exercised executive power during the Revolutionary War by creating the Continental Army, nominating George Washington as its first president, and coordinating the war effort with the various state militias. With the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, the United States gained a framework for the orderly colonization of new territories, a path to statehood, and safeguards for those who settled in the Northwest Territory.

In conclusion, both the First Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress were critical to the development of the United States and to the establishment of its independence there where a congress president for each but not like the American presents you think of today. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the formation of the Continental Army under George Washington’s leadership were both products of their efforts. The early development of the United States was greatly aided by the administration and leadership of the United States. Both the Continental Congress and the Confederation Congress were crucial in the war’s management, coordination of military and financial operations, and establishing the groundwork for George Washington’s eventual administration. Their legislative and administrative efforts paved the way for American independence, created the first centralized government, and set the framework for subsequent growth. The contributions of these congresses show how the American people are strong and determined, and they have helped shape the destiny of the country.